A recent episode Japan By River Cruise (Woke Dad Japan) featured Daniel Yoder, one of the hosts of the Konnichiwa Podcast (コニポ). They spoke about the challenges of raising kids in Japan as foreigners. It’s a fun episode, and I can identify with a lot. One of the challenges they spoke of was their kids’ language abilities. My kids’ (aged 8 and 11) situation is different to theirs since we are a family who has been back and forth between Canada and Japan. But the episode made me reflect on how my thinking on child language acquisition has evolved over the years. Generally, it has gone through three stages: bilingualism, heritage language, plurilingualism.

First, a disclaimer from me:

This post is totally a simplification. I do touch on some of the complexities in the Loose Ends section, but your situation is likely different. My undergrad is in Linguistics (Language Acquisition), but I am not a current academic and things have gotten a lot more complicated in the intervening 20 years. My goal here is to introduce you to some concepts and possibly spark an interesting discussion. I don’t make any claims on the best way to teach your kids multiple languages. You know them better than I do! As you will see, context is everything. That said, I think it is valuable to learn from different contexts.

Okay, ready? Let me walk you through my progression.

Bilingualism

Multicultural parents face lots of social pressure regarding their kids language abilities. On the one hand, they are told they must teach their kids both languages, since it would be such a waste to forgo this opportunity. On the other hand, there can be opposing pressure as well, the “why bother teaching them Japanese you are in Canada now!” I am not going to discuss that here, but it is worth acknowledging. Generally, both of these views come from monolinguals who don’t understand how difficult the prospect of bilingualism actually is. That said, the stress of a bilingual parent is real, and comes out of a divergence in language acquisition. I will use my own kids as an example, since it is a fairly simple one (I will get into complexities — and the differences in Japan — later).

The problem arises when the L2 language overtakes L1 in an L2-dominant society.

Let me explain with a concrete example: When my kids were little our home was Japanese-only. Their first language (L1) was Japanese even though we were living in Canada, in an English-dominant society. Once they started going to school, English (L2) started taking over. It became their “play” language, and they would use it when playing at home together, even if they would speak Japanese to us. Over time, they stopped speaking Japanese to us even though we would speak it to them.

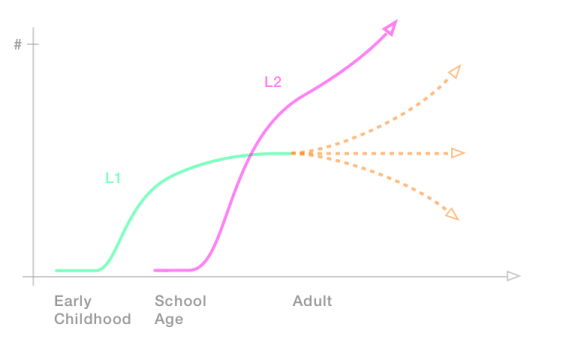

Let us visualize this on a scientifically proven fake chart:

As you can see, L1 acquisition starts in early childhood, then in school the L2 starts coming along, L1 starts to plateau, and finally L2 overtakes L1 and continues to go up. The three dotted lines are possible scenarios for the L1. This is where the parent becomes worried for the child’s future: Will my child lose her L1? Keep it at its current level and be forever semilingual? Or can we send her to Japanese school, kicking and screaming, and try to get her L1 up to scratch? Many people (including myself) choose the last option. As you can imagine, like most schools of this sort, the kids weren’t necessarily happy to forgo playing with friends after school every Wednesday to go to a different school that “nobody else” had to. Luckily we had a lot of immigrant friends who were also sending their kids to Korean, Punjabi, or Chinese school that we could use for leverage (Social pressure can be used for good too! 😄). Although Japanese school helps, once a week is not enough to get their L1 up to L2 levels. We had to come to terms with a more realistic goal for our kids.

Heritage language

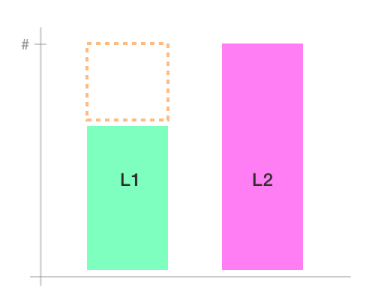

Let us visualize this with another fake chart.

L2 eventually overtakes L1, and there is an ability gap, as indicated in orange.

That gap is a source of stress for parents who feel pressured to make sure their child is “fully bilingual” — whatever that means. Defining “linguistic competence” is a very difficult thing, a legitimate problem in linguistics. By thinking of the problem in these terms, we are causing undue stress on ourselves and our children, and in many cases, turning our kids off the rewarding pursuit of language learning. We need a new approach.

Some language educators suggest a different category for such L1s: heritage language (or in Japanese 継承語 keishōgo). Languages are not just lists of words and grammar rules, but include a bunch of cultural knowledge as well. Some heritage languages, like creoles or indigenous languages, are at risk of being lost — there is a special impetus for teaching those. The point is: learning a heritage language is different than learning a foreign language. Teaching kids their heritage language like I learned learned Japanese at university is not appropriate. A heritage language is wrapped up in the identity of the speaker, and therefore should not necessarily be assessed like a foreign language. You don’t want your kid to “fail” her identity! You want to encourage her to have a positive relationship with the language and all its cultural trappings. The educational style tends to follow the interests of the child. If they are bored by the textbook, but interested in anime, use that. Basically, do anything to keep them learning, and worry about the holes later. This is not Tetris, they can go back and fill in those holes later as adults.

We reset our goals to account for this more holistic approach, which includes a lot more cultural education, participating in Japanese festivals and holidays even if the surrounding Canadian society doesn’t. Our kids might not be able to speak/read/write Japanese natively, but they will have a certain level of fluency in the culture (“culture keeping”). The “gap” in the fake chart above is thus filled not with complex grammatical structures, but with intercultural skills useful for switching between English and Japanese social contexts.

Plurilingualism

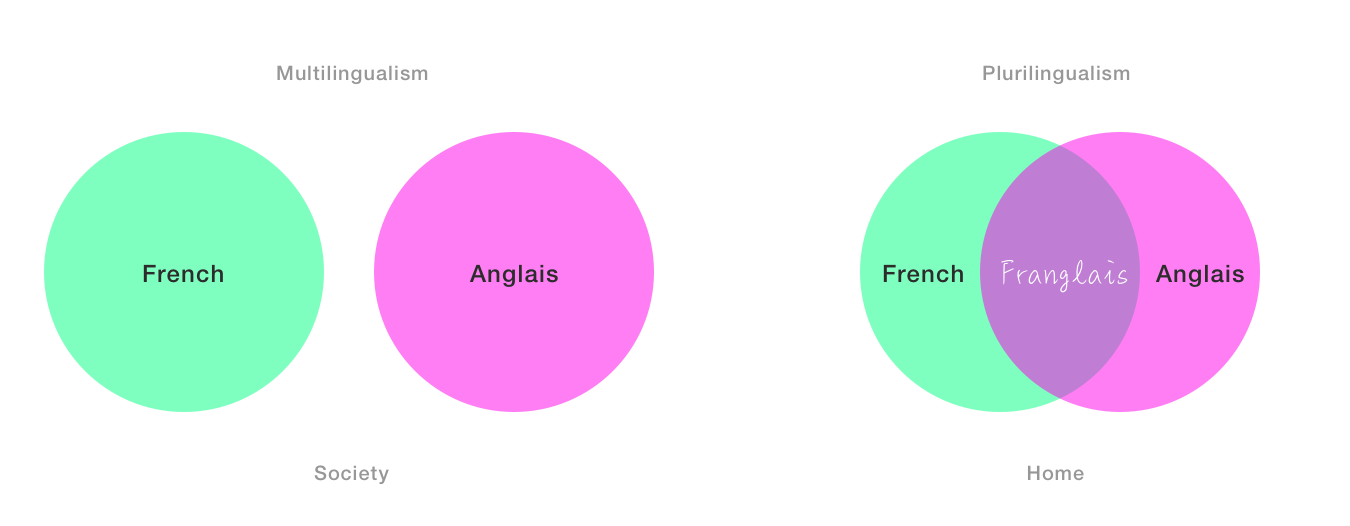

Recently I came across the term plurilingualism as introduced from the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Put simply, the idea is that it is perfectly okay to switch between languages depending on the situation. Often we are told not to switch languages, that it is detrimental to the learner and will lead to semilingualism. Languages must be kept separate at all times! For the good of the people and the good of the language! Plurilingualism opposes this, recognizing that the cultural knowledge embedded in languages is not equal. In other words, in the right context, mixing languages during communication results in a 2+2=5 kind of situation. Language ability is compounding. We express this concept in a fake chart like so:

Canada is technically a bilingual, or multilingual society. English and French are both supposed to be everywhere, but they are distinct languages (with distinct laws). Nevertheless I am confident people in the bilingual parts of Canada are language-mixing in the home like we do with English and Japanese in ours.

Singapore is an example of a plurilinguistic society. Take this example from the Geography Now Singapore episode when he asks for a “an ice tea with no sugar”:

Uncle! 我有一杯 The O Kosong Peng

This single phrase combines English, Mandarin, Hokkien, and Malay!

There are lots of words in Japanese that are just quicker and easier to say than the English counterpart. So why not throw them in? To bring the discussion back to podcasts, Daniel Yoder’s Konnichiwa Podcast (コニポ) is conversational show with three friends who switch back and forth between English and Japanese. Pretty cool!

In the end, learners gain a lot by learning different languages, even if they are not “native” level. Kids can draw from across all their linguistic and cultural tools, which builds confidence and hopefully a desire to learn more. I think the heritage language concept fits well into the plurilingualism concept.

Loose ends

Okay, so to recap:

- native-level bilingualism/multilingualism is tough

- culture and language are connected

- foreign language learners are not the same as heritage language learners

- there are communication and educational advantages to plurilingualism

I have focused on my particular situation, having kids born in Japan but raised in Canada. In Japan there are lots of other variables that can complicate the situation. I am going to list a bunch below for acknowledgement’s sake, but I hope that people add their own perspectives with details in the comments below.

- [CORRECTION. See footnote†] For international couples in Japan where the main caregiver is an L1 speaker the kids grow up L1 in an L1 society, with the English-speaking parent being the only source of L2. This has all sorts of other educational complications, but from a plurilingualism perspective, the kids still have an advantage.

- English has a special status in Japan, and I am not sure how well it can be considered a “heritage language” in this context since it is so desired as a 実用語 or lingua franca.

- I am not sure how bicultural kids in Japan learn English beyond speaking English at home. I have heard of parents sending kids to English schools like ECC to practice, but I don’t know of any heritage language programs here. As for kids in international school here, I know their approach to Japanese is not the 国語 approach, but it might not necessarily be a heritage language approach since not all students would fit the profile.

- All my examples above were English + Japanese. People in Japan of Korean, Okinawan, or Ainu descent have a different situation. Furthermore, I would love to learn about heritage language education for other communities like Brazilians, Filipinos, Chinese, Mongolians, etc etc in Japan. I tried to find stats on languages spoken in households, but was unsuccessful.

- I completely avoided “literacy” on purpose, to try and keep the discussion as high level as possible.

- I want to draw your attention to Laurie’s tweet, which sounds like some awesome plurilingualism!

- Last year as a family we attended Chinese language class, which was lots of fun. Going to Chinese language summer camp in Taiwan was on the list of things to do while in Iki (obviously had to scratch that one off!)

- Canada and the US are pretty dismal when it comes to median number of languages spoken per person. I would love to hear about the experience of plurilingualism from a European or African perspective.

Addendum: Coming to Japan and a possibly new context

One of the reasons we came to Iki was to give our kids an opportunity to be in a 100% Japanese-language environment, for a limited time, to boost their language skills. Although stressful, but I am overjoyed at the progress they have made.

It has been challenging in unexpected ways. I wasn’t too concerned about their grades in “Language Arts” (国語) but in fifth grade many math questions are word questions, and if you can’t read the kanji you cannot solve the problem. Also, as a foreign dad, I don’t know the terms, nor the techniques for solving these equations, so there is not much I can do for them. This is a common challenge for many immigrant parents of course, or even parents in Canada that send their kids to French immersion.

As my kids progress in school here in Japan, the struggles will just pile up. I have no real reason to force Japanese-language education on them, so once our time is up here we will go back to the smoother English language education route. If for some reason we can’t make it back to Canada due to coronavirus restrictions, we will transition them to international school here temporarily until we can go back. I look forward to comparing how they perform in that educational environment!

_________

† Correction — Original text:

In Japan women intermarry a lot more than men. Since women are also statistically the main caregiver, kids grow up L1 in an L1 society, with the dad being the only source of L2. This has all sorts of other educational complications, but from a plurilingualism perspective, the kids still have an advantage.

Ollie Horn pointed out that men intermarry far more than women in Japan. We regret the error, and have made the main text more generalized. ⤴