At 6:15 the bell tolls. You have already been awake for a half hour. Anticipation? Slowly, you pad out of your cell at the Birken Forest Monastery, walking over the matted straw floor and into the carpeted hallway. You peek down into the meditation hall from this second-floor hallway to see if anyone is already in there. A few are. Anticipation.

Down the wooden staircase to the first floor, you alight onto the tiled entrance way. Many wear socks, but the monastics don’t, so you don’t. You open one of the double doors to the sala and give a short, Japanese-style bow to the five-foot-tall statue of the Buddha. You are still unsure of the etiquette in a Thai Forest monastery, so you stick with what you know.

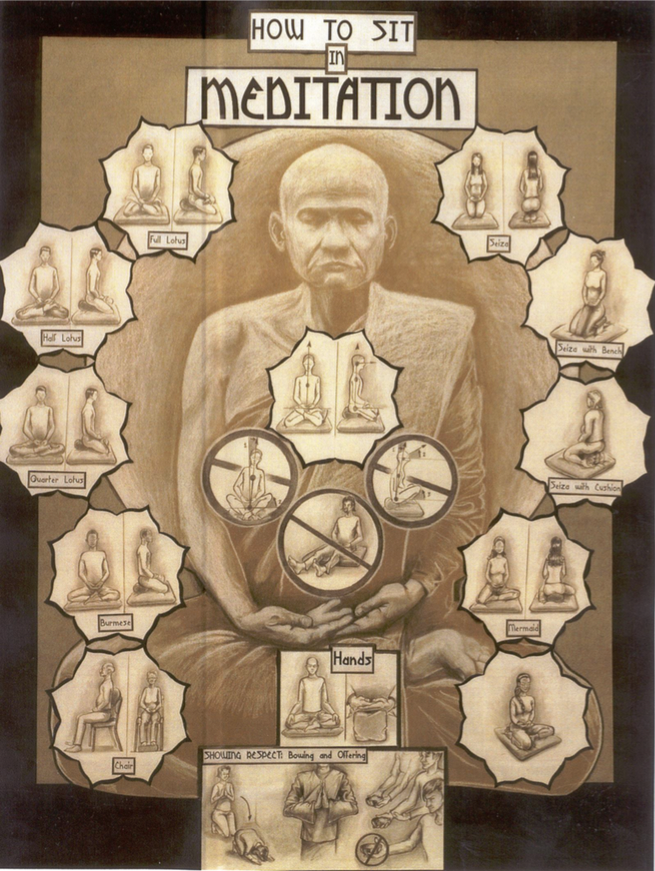

Along the back wall of the sala are the large, square mats, and the round, stuffed meditation cushions. Taking a set, you settle down on the black, marble(?) floor. Quarter-lotus is all your poor inflexible legs are capable of, but yesterday you could only do Burmese style, so you feel a little sense of accomplishment. Resting your hands near your belly, thumbs lightly touching, you gently close your eyes and (try to) calm your mind.

A few still moments pass and you hear the doors slightly groan and the swish of robes as the abbot Ajahn Sona and Sister Mon enter. Your eyes slightly open, out of habit, but it is not necessary. They sit down and — with the utmost ease — settle into half-lotus.

“Focus on the intake of air into your nasal cavity…”

There are no greetings; just the Practice. And you get to it, as best you can.

The air comes into your nose cool, before it is exhaled warmed by all the pulsating, pumping heat of your body. The inhale is refreshing. It is like, after being in a stuffy room, stepping out onto the balcony and breathing a lungful of fresh air. People will tip their heads upward, taking in the moment and smiling. It is that moment of bliss that you are trying to sustain for this 20 minute meditation session… and ideal for life.

You mentally bat away random thoughts while trying to hold onto the bliss. Putting a slight smile on your face sort of kickstarts the body, reminding it what “happy” feels like. You hear the growl of hungry bellies. For not eating dinner last night, you are surprised that you don’t feel more famished. At the thought, your belly grumbles a retort. Be humble.

Come back to the breath… the fresh air, the bliss. You can hear the wind blowing in the poplar trees outside. Outside of the monastery, in the rat race, your shoulders are in a permanent half-shrug of tension. It is the source of your neck pain, compounded by hours of staring slightly downwards at screens of various sizes. You must mindfully remind yourself to release the tension and let your shoulders settle to their natural position. Yet here, only after a day or so, your shoulders are at their natural height without the need of your will to force them down.

“Come back to the breath… Count the exhalations up to five if it helps you maintain focus.” says Ajahn Sona.

Some minutes pass, you realize. Wow! You were in the zone there! Try to hold on… but now your right leg is fully asleep. There are no pins and needles — it just feels dead. Will it fall off?! You subtly shift into the Burmese style of sitting. Come back to the breath…

Slowly, as blood fills your leg again, you are able to come back to the breath. Then, before you know it, you hear the waves of the meditation bell as it is struck, signaling the end of the session. The gentle sound is as refreshing as … as a lungful of balcony air.

“Try to maintain that focus as long as you can while you go about your day.” says the Ajahn, who then gets up and swishes out of the room. You press your hands together in front of your chest and slightly bow.

Next is walking meditation. But first, the struggle of standing. After a few stretches you are able to get upright and let the blood rush down your straightened legs. Gingerly, you make your way to the back of the hall to return your cushions. Then, bowing on the way out, you leave the hall and head to the walking sala downstairs.

You are in a sort of blissful daze, with a nearly tangible sphere of “concentration” about two feet in front of your chest. That are seems to be the only thing in focus. Is this feeling samatha? Is that ball of focus the vipassana?

Down one set of stairs, past the kitchen, and then the final flight of stairs to the bottom floor where the tea room/guest dining room is. You walk through the shelves of the Birken library and into the four lanes of the walking sala. Each lane is wide enough to accommodate two people. Clasping your hands behind your back, putting your focus a meter ahead, you put one foot in front of the other.

You find the 20 minutes of walking meditation go by faster than sitting. Having to watch where you are going, and feeling the muscles, sinews and pads of your feet in contact with the concrete gives you enough stimulation to prevent random thoughts coming into your mind. Plus, there is no fear of any body parts falling off due to lack of circulation. Your warm feet slightly stick to the cool concrete, resulting in a sort of suction-cup sound that is distracting. You will wear socks next time. Soon the bell rings, and you retreat to your cell upstairs for a little break.

Breakfast is at 7:30, and you load your plate with granola, Greek yoghurt, cherries, dried cranberries, almonds and a slice of toast. Eating is silent time, and everyone focuses on their meal, eating each nut with mindful attention.

Guests are expected to help with clean up after every meal, so the kitchen comes alive when the dozen of your retreat-mates are washing dishes and pots, wiping down and disinfecting surfaces, and putting away all of the remaining food. After spending two hours in silence together, this is the time most people share morning greetings.

Once breakfast cleanup is done, you head upstairs to the south bathroom. Upon arrival everyone signed up for a cleaning duty, and this bathroom is yours. Zen-like, you clean as per the instructions. The monastery has detailed instructions everywhere — taped on walls or inside of cupboards — and it seems every door and bin has a label on it.

After cleaning duty, you could retreat back to your room and read some more, but you decide to go outside — besides, you should probably take some photos for your blog. Looking out your window, the day is bright and wind blows through the leaves of the trees that surround the monastery. The poplars are young and narrow, tremulous yet densely packed together. It is like a watercolour painter was practicing with a very thin brush — stroking upwards again and again and again without a mind for spacing or balance: in the moment.

Outside you walk around the grounds, past the solar array that powers the entire monastery. You have not checked your phone since arriving, which is fine since you are out of cellular range anyways. There is a raked stone garden on one side of the monastery, and an 8-sided stone garden with a meditation bench on the other. Up the dusty logging road are the kutis, the cabins with the monastics stay. You stay away from them, not wanting to disturb anyone. At 4,000 feet elevation, it is pretty cold up here — much chillier than Kelowna. Good thing you brought a hoodie. The moon hangs in the clear sky. You look at it through a Japanese style torii gate near the entrance of the monastery, but do not point.

Soon it will be time for the next meditation session: 20 minutes seated, 20 minutes walking. But before the real sitting starts, Ajahn Sona gives a morning dhamma talk. This morning, he speaks on mettā, otherwise known as loving-kindness. He encourages you to generate feelings of loving-kindess while you meditate this morning, but stresses that as beginners you should start small. “Start with kittens.” he quips. He is much funnier, and much less severe than he is in his YouTube videos. Using a smile on your face to induce the body into a positive state, you start to focus on your spouse, then kids, then family members, then all of the refugees of the world. You feel the mettā, and realize how much your daily life lacks it.

Post-breakfast meditation is always the best. A full belly makes concentration much easier. Then it is more free-time, which you spend reading books and pamphlets from the library.

Lunch is held before noon. Monastics of the Thai Forest tradition only eat two meals a day, between the hours of 6am and noon. After noon, they are only allowed to have water, tea, or highly strained fruit juice. So, this is the time to feast. The stewards, who live at the monastery to support the monastics in various ways, have outdone themselves today: three different salads, a spicy noodle dish with fried tofu, brown rice and a magnificent lemon meringue pie. Prior to the meal, the abbot Ajahn Sona, Sister Mon, and another monk came in for the mealtime blessing which lists out the reason why we eat which includes to keep back the pains of hunger and not induce new pains of overeating. You try to keep that in mind has you spoon a slice of pie onto your plate.

After the silent lunch there is cleanup again, then some free time before the 2pm meditation (again 20 minutes seated and 20 minutes walking). Some people use their free time to meditate more. You spend some time in your room reading.

At 5 is tea time. You have learned to drink tea like a pro — it helps to douse the pangs of hunger. This is the time of day you need it most. Ajahn Sona comes in and sits on a wicker couch (in half-lotus of course!). Tea time is Q&A time. The Ajahn encourages everyone to ask him anything: about meditation, Buddhism, life… basically anything but hockey. Being an Absolute Beginner’s Retreat, this is not the place for high-level discussion and debate on the finer points of Buddhist doctrine, but Ajahn Son takes the basic questions fielded to him by the crowd and makes sure people can walk away with a practical teaching. The stewards, much more experienced than, sometimes pipe up with more advanced questions which piques your interest.

He talks about the isolation at the monastery. About how humans spend their life in four basic positions: seated, walking, standing, and laying down. These are the basic meditation positions and the point of focussing on these positions is to refine one’s experience of the day to day. He says we are trying to “raise the level of the ocean” to improve the overall enjoyment of life. Happiness should not just be spikes in your life — 3 days in Hawaii every 6 years is not good enough. If you can find joy in sitting, walking, standing and laying down, you will have a much better life. This is a nice teaching that you make note of. A wine connoisseur refines her senses so that she may be able to enjoy her wine at a whole other level. You will refine your senses so that you can enjoy life at a whole other level.

After the Q&A it is “snack” time. Ajahn Sona and Sister Mon have left, and the retreatants are welcome to a few nibbles to settle their tummies since they are “Absolute Beginners.” The stewards lay out some cubes of cheese, some crackers, and some little squares of chocolate. The monastics are not allowed this, and since they do not partake, neither do you. You are here for training. You fill your tea mug and drink mindfully, trying to ignore the sounds of eating all around you.

Then it is time for the evening sit. You struggle with this one as hunger nips at your focus like a pack of barking hyenas. You can hear the grumbling of bellies echo throughout the hall. But you are tiring as well, and it is a little too easy to lose consciousness. Come back to the breath…

At 8PM you head upstairs and take your shower. By this time the hunger pains have nearly grumbled themselves out. You climb up the ladder to your bed loft into your sleeping sack. It only takes about 10 minutes of reading before you start to slip off. Doing nothing all day is tiring! Turning off the light, you lay in the darkness. The sound of wind in the leaves… you focus on the breath in your nasal cavity, and soon drift off to sleep in preparation for the whole cycle to begin again tomorrow.