Downsizing (or minimalism) is often portrayed as anti-consumerist and eco-friendly. Living small means you buy less stuff, produce less trash, and have a smaller environmental footprint in terms of heating/cooling your home. Plus, if you position your home close to amenities, you walk/bike more and drive less. Secondly, living small is about removing oneself from the current trend of financialization — getting off the mortgage hamster wheel, removing debt dependance, and not participating in surveillance capitalism by using credit cards and the like.

These are all good reasons for downsizing, but is the tactic wrong? It depends on what you are trying to solve for.

Your fantasy tiny house… is a fantasy

Arielle Milkman’s critique of the tiny house movement pulls on many threads shared with minimalism in general. She writes:

Tiny homes aren’t a solution. Small living is another superficial fix, brandishing clever design and appeals to nostalgia while ignoring the underlying social relations which cause homelessness, housing insecurity, and environmental degradation.

It is worth reading the whole piece, but I will include a few of her arguments below:

… whether tiny homes are an environmental boon is questionable. These dwellings don’t improve energy efficiency on a large scale

Very true. NYC is the greenest place in the US by certain standards as she points out. Tiny homes may be low impact, but are not a scalable solution. Density is the key:

… urban planning theories now valorize dense, mixed-income, and mixed-use neighborhoods. But tiny houses generally do nothing to increase urban density in cities like Washington, DC, which is already concentrated with people and has little open space.

When I pitched a tiny house community near downtown it was with the intention of sustainability. Traditional trailer parks are at the edges of a community, typically requiring a vehicle. But if urban density is what you are looking for, tiny houses are not the way to go. Putting tiny homes where carriage houses would go might be a stopgap, at least in my community where attitudes towards urban density are pretty negative. People here don’t want denser residential areas, despite all the benefits.

Milkman seems to be promoting large, socialized towers. Charles Montgomery talks about the shortcomings of towers in in his book The Happy City. You can get a taste in his TEDx talk (around 7:38):

If “social relations” is what you are solving for, the residential tower is not the answer. Mixed-use low-rises will add to density at a much higher rate than tiny homes, and contribute to community building better than giant towers.

But new, green, low-rise apartments are not cheap. Let us next turn to affordability.

If not a tiny house, then what?

For tiny house proponents the idea of owning a home for $30,000 is appealing, at least in terms of cutting costs. Even the smallest apartments around here are $200K+ so buying is a problem.

According to the Canadian Rental Housing Index, in my community of Kelowna, the average rental cost for a 2 bedroom apartment is $1,072. That is liveable for a 4 person family (my two daughters currently share a room), but the price is likely to be higher since we would want to live in a walkable neighbourhood (as we don’t own a car). Even going by that relatively low rate, for the price of a tiny home we could only rent the apartment for 28 months.

True, this calculation does not include land fees. As Milkman points out, tiny home “owners rarely have rights to the land upon which they are parked.” I do not know the rates of parking a tiny house behind another house, or even the legality, in Kelowna. I reached out to city planners responsible for Secondary Suites, Carriage House, and Two Dwelling Housing, but never got a reply.

The problem of affordability could be solved if housing were socialized, which is what Milkman seems to be arguing. Although social housing does exist in my community, access is limited. Even as a single income family we make too much to be able to take advantage of these resources. Access is based on gross income, not disposable income. I make a decent wage, but almost a quarter of it goes to student loans. In this, I fear I am like many Canadians.

There is a missing middle. Looking at the housing continuum from the City of Kelowna’s Affordable Housing webpage, I think that green bit in the middle is a lot smaller than it should be.

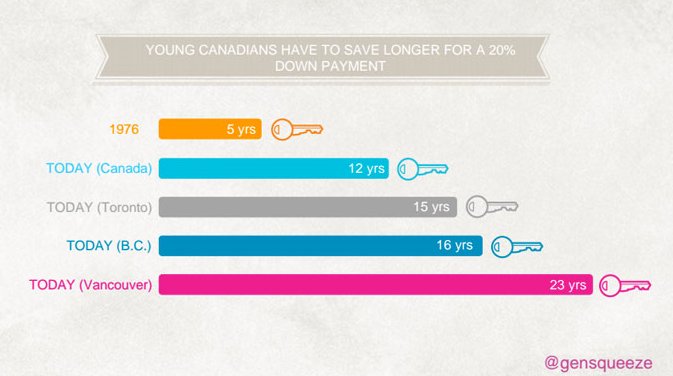

For some real numbers, check out this report by Urban Matters which plots the Affordability Gap in their profile of Penticton, a nearby city. Generation Squeeze, a lobby group for Canadians in their forties or younger, also has some information on the housing gap for younger Canadians.

Whether it is giving more people access to social housing, or incentivizing developers to create more affordable housing stock, there must be a solution. In the meantime, we remain squeezed. It is in this environment that tiny houses seem like a good (read: achievable) solution.

If you are not part of the solution…?

Milkman points that “the tiny house movement took off after the Great Recession hit.” The most recent comeback of the tiny house “fad” is certainly related to the mortgage crisis and its deleterious effects on the economy.

It is worth considering: is minimalism/downsizing merely a reactionary reflex to a down economy? Because of flat wages, rising housing costs, the increasingly privatized public sector, and austerity measures, our generation cannot afford the lifestyle of our parents. Is downsizing a way of embracing that fact, and thus, letting our community leaders off the hook?

Milkman, in her critique, portrays the tiny house movement as a capitulation to runaway capitalism, “individualistic” and “atomized.” Living small is like having Stockholm Syndrome for neolibertariansim.

To be less extreme, maybe it is more like a survival tactic. North Americans, including myself, have spent too much time living on credit. My push for minimalism was partially motivated by the age-old (and seemingly forgotten) advice to live within your means. That is what I can do in the short term as an individual. Sure, this is not a solution to the wider social issue, but living it and talking about it is not a superficial thing and surely a step in the right direction. The question then becomes, what is the next step. For that I will close with a quote from Milkman herself (my emphasis added):

Ultimately, alleviating housing insecurity, creating dense, environmentally friendly cities, and realizing the desire for independence and self-sufficiency will come from collective demands and struggle — not from buying or building a better home, no matter how small it is.