The “right to the city” is described by David Harvey as:

The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.

Although it was a bit of a slog, I enjoyed the ideas presented in his book Rebel Cities, and have continued to think about how I as a citizen can play an active role in the shaping of my city’s development. Thus, I was very excited to welcome Kusunoki Masashi of Citizen Energy Ikoma to come and speak about how his group put solar panels on the rooves of public buildings. see previous post about the talk.

What Japan and Germany have been doing

Japan is particularly vulnerable when it comes to energy disruption since it needs to import more than 80% of its energy requirements (if you want to know more in excruciating detail, see my master’s thesis on the topic). But the 2011 Fukushima disaster was a massive blow. The 9.0 Tōhoku earthquake caused a tsunami which triggered the nuclear meltdown causing nearly 16,000 deaths and hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people. Five years later, Japan is still heavily engaged in the cleanup. In the wake of the disaster, all 50 of Japan’s nuclear reactors were shut down. Starting last year, despite much public protest, the Abe Administration has begun restarting nuclear power plants.

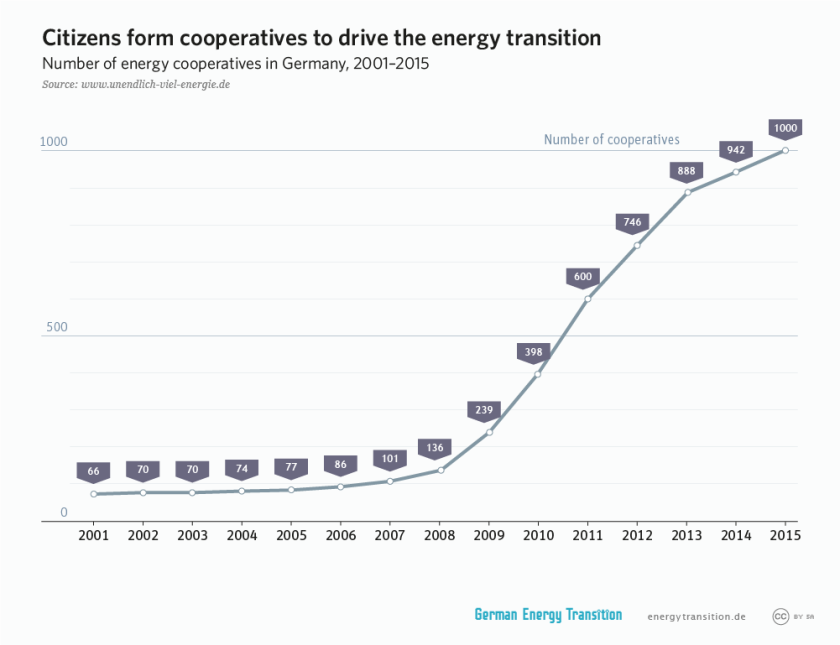

In the meantime there have been a number of citizen-led movements for safer, more resilient energy resources similar to Citizen Energy Ikoma. Many are inspired by the experience of Germany. As part of the Energiewende (“Energy Transition”), decentralizing and democratizing energy production has been a key effort. Municipalities and citizens have been taking back energy utilities and in 2012, one in sixty Germans was an energy producer. The number of energy coops has risen to over 1000 in 2015.

The Energiewende policy started in 2010, but after the Fukushima disaster in Japan, Germany set policy to shut off all its nuclear reactors by 2022. (The Energiewende is a very complex topic beyond the scope of this post. If you want an overview, check out this dispatch in FP and this National Geographic piece.)

Using our right to our city

Distributed energy supply, disaster-proofing resilient communities, and fighting climate change at the local level… it is all pretty inspiring stuff and makes me think about how this can be applied to my own city.

Kelowna gets about 305 days of sun a year, with 1950 hours of bright sunshine. Plus it gets very little snowfall: only about 5 days a year with more than 5cm, and 1.4 days with more than 10. (data) What this means is that we have a lot of flat rooves. All that flat area and all that sunshine makes for a good argument for putting solar panels everywhere.

Just this summer Kelowna City Hall replaced its roof. What if they had installed solar panels up there? Scratch that: what if we installed solar panels up there? How many other public buildings, schools and open areas could be used towards these ends? If the city does not have the capacity to do this, Ikoma and all the other cities in Japan and Germany prove that we as citizens can. They serve as examples of how to use our right to the city.